- Home

- Peter Mehlman

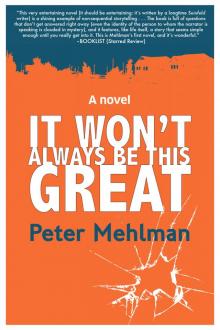

It Won't Always Be This Great Page 8

It Won't Always Be This Great Read online

Page 8

You know, one afternoon during my junior year of high school, I was playing ball and, suddenly, in the middle of a fast break, I just stopped in my tracks, looked at my friends, and received a thought from heaven: I gotta get out of here.

And that’s how I wound up going away to college. One moment of clarity without which I wouldn’t be in this hospital room right now, I wouldn’t have met Alyse, and my kids would look like someone else entirely.

Shit, even as a junior at Maryland, it probably took me more resolve to ask out Alyse than it took Rosa Parks to sit in the front of the bus. Of course, Rosa Parks had righteousness on her side. All I was doing was asking out a girl I’d done little more than stare at across a PSYC 401 lecture hall for half a semester. Why’s it so hard sometimes to do what you know is right?

The first time I talked to Alyse was after class one day just outside Zoo-Psych. I had a Coke in my hand from a vending machine when we practically walked right into each other. I said hi and was about to boldly introduce myself when I fumbled the Coke, spraying it along the bottom of her shredded Levis. I felt sick but managed to say, “Those were nice jeans.” She laughed, which was a huge relief. I was caught off-guard by her voice, kind of girly and feathery. Eventually, I bucked up and said, “Look, I’m going to fail this class because I spend all the lectures looking at you.”

You know, I’m fairly sure she still has those jeans. Or maybe she cut them down to shorts. Not important.

On our first date, I took Alyse to see Play It Again, Sam at the Student Union. A smart move. I was so nervous, I let Woody Allen break the ice for me. Alyse loved it and thanked me for getting her to see it. Afterward, we walked through campus to Route One and wound up getting coffee and dessert at the Howard Johnson’s. Can you believe it? But, there we were, under the orange roof, when four nuns came in for a late dinner. I assume it was a late dinner. I mean, who the hell knows what kind of hours they keep? Alyse and I eavesdropped on their conversation because neither of us could even imagine what nuns talk about. I whispered something like, “Isn’t the convent like a dorm where they get free meals?” And Alyse says, “Maybe HoJo’s is running an All-You-Can-Eat Fried Clams For Celibates Night.” Naturally, I was a bit unnerved by Alyse saying anything even loosely related to sex, so I forced a laugh and said, “I thought their whole lives were devoted to God and whacking kids with rulers.” At which point, Alyse asked me if I believed in God. Without skipping a beat, I said, “No, I don’t believe in God and I tell Him so every day.” I don’t know where that came from. Maybe I was a little imbued with Woody. Alyse laughed out loud.

“That’s hysterical! What a great answer!”

It was the first time I got a big laugh out of her, and I won’t get into the whole pseudo-cool analogy about your first shot of heroin—as if anyone was less likely to try heroin than me—but it was a feeling I wanted for the rest of my life.

Then, on top of that, when I dropped Alyse off at her dorm, I said to her, “Well, there it is, Alyse. There’s your date.”

She thought it was so funny, she called me at the frat an hour later at like 1:00 AM to tell me she was still laughing about it.

Don’t get me started on how many dates it took to kiss her, not to mention . . .

Hey, I just had a funny thought. Let’s say you got really great tickets to an NBA game and you went to sit down and Rosa Parks was in your seat. Would you have asked her to get up?

Commie!

Christ, that’s the kind of hypothetical question I used to crack you up with all the time. Remember how, in the middle of the night, we’d be bullshitting and I’d hit you with a crazy scenario like that?

Wake the fuck up, Commie.

Okay, so I was lying on the couch with my ankle propped up in frozen peas. While Alyse and I talked, I half-watched a TiVo-ed episode of Law & Order SVU. That poor Detective Benson was still trying to figure out how to live with owing her existence to her mother’s rapist. And that Mariska Hargitay makes it believable. You know her mother was Jayne Mansfield? The shit people live with.

Out of nowhere, I hit the pause button and said to Alyse, “As long as we have two couples, why not make it three? I can ask Arnie if he wants to come along tomorrow night.”

I turned to see Alyse looking at me as if we’d never met. At some point, her sweat pants had lost the string in the waistband, so she rolled them down to her hips, exposing an inch of creamy brown flesh on either side of her sloping innie bellybutton. Alyse never wore overtly sexy clothes and wasn’t one of those mothers who turns forty and starts dressing sixteen. Aside from her choice of me, she has taste. So this unconscious but nevertheless rare sight of skin was, well, you know, it distracted me. What I’m saying is, I liked it.

I shifted on the couch and said, “What’s wrong?”

“Nothing. I’d love to have Arnie and Fumi come. I’m just surprised you suggested it. Pleasantly surprised. Maybe your ankle pain flicked on the social director part of your brain.”

“Or maybe it was throwing a bottle through a store window.”

XVIII.

Just kidding. I didn’t tell Alyse I threw the bottle. Or the two detectives who came to the door.

And no, I’m not kidding about the detectives. I’m lying there doing cryogenics on my ankle and admiring my wife’s midriff when the doorbell rings. Alyse asks who it is and I hear, “It’s the police, ma’am.”

For the first time since I’d started having panic attacks, my fight-or-flight response kicked in for an appropriate reason. I must have missed one of the store’s surveillance cameras. They digitally saw someone throw a bottle through the window, brought it to the lab, enhanced the picture, printed it up, canvassed the neighborhood, showed everyone the photo, and the guy with the Bernese fingered me. Holy shit! I can’t even run. My life is over. Everything. It’s all shot to hell. Alyse, Esme, Charlie . . .

Detectives David Shelby and Dennis Byron followed Alyse into the den. Like Lee Harvey Oswald in the movie theater, I froze, hoping they’d miss me. I could barely listen to what they said.

“. . . minutes ago, a cabdriver named Nick Geragos was stopped for driving up a one-way street. He said he was lost, then recounted picking up a man a little after five on the 600 block of Stratification Boulevard and taking him to this address. Are you that man, sir?”

Lying on my back, I looked up, and the cops seemed humongous. I must have looked stricken because Shelby, the tall, balding, affable cop, chuckled and said: “Excuse my partner. He could be talking to you or Hannibal Lecter. He’d sound the same.”

Coldly, Byron said, “Yeah, sorry.” He looked like Perry Smith from In Cold Blood, a compact guy with a short fuse.

I sat up. My fear of being busted mixed with an urge to seem hapless, so I said all stuttery, “No, don’t apologize. I’m sorry. See, I rolled my ankle on the root of a tree, that’s why I flagged down the cab and I play basketball so the injury freaked me out that I’d never play again and I watch too much Law & Order so, with all that, and two detectives here—look, don’t listen to me. I’m an idiot. What can I do to help?”

Shelby laughed out loud, but Byron just clenched his jaw. He didn’t even smile when Alyse playfully nudged him and said, “Maybe you should cuff him, bring him downtown, and tune him up.”

Alyse watches Law & Order with me a lot. It’s something we love doing together.

It wasn’t overly warm in the house, but Byron removed his sport jacket. He had on a blue short-sleeve shirt and mud green tie. He threw the jacket over his left shoulder as Shelby said, “A store was vandalized by a thrown bottle and since the cabbie picked you up in the vicinity of the store near the time of the incident, we took a flyer thinking you may have seen something.”

As Shelby finished his gentle explanation, I saw Byron glance at Alyse’s midriff. His look gave me a tiny chill, but so much other stuff was filling my head, I didn’t dwel

l on it. Alyse went to the kitchen to whip up some coffee. Shelby said there was already talk of an anti-Semitic motive behind the crime. I said, “Why would an alleged anti-Semite throw—did you say it was a bottle?”

“Yes. A bottle of horseradish.”

“Red or white?”

“Excuse me, sir?”

“I was asking whether it was red or white horseradish, but I guess that’s not important.”

Byron looked at me like he was dealing with a total moron, and I guess he was, but he didn’t have to be such a prick about it. Then again, Commie, can you believe I asked if the horseradish was red or white?

“Anyway,” I said, clearing my throat, “what anti-Semitic statement is made by hurling a bottle through a store window?”

Detective Shelby said, “The store owner is Nat Uziel and—”

“Oh! Nat’s a patient of mine. I’m his podiatrist.”

“So maybe you know that recently he became a big muckety-muck in some organization that deals with bonds for Israel.”

“Israel Bonds?”

“Sounds right.”

“So it could be less anti-Semitism than anti-Zionism,” I said. “Either way, it doesn’t narrow down the choices very much, does it?”

“No,” Byron said. Or more accurately, grunted.

“Did anyone look at surveillance camera footage?”

“Not yet,” Shelby said, “but odds are that won’t help because, according to one of the CSI guys—do you watch those shows too?”

“Not really.”

“Me neither. Truthfully, since NYPD Blue, I stopped watching all cops shows. Anyhow, according to Crime Scene, the bottle was thrown from at least fifteen yards away—out of camera range.”

Alyse brought in two mugs of coffee and seventy-five varieties of sweetener. Shelby sipped his black. Byron threw in three sugars and drank like he’d just been rescued from an avalanche.

Then there was a creaking on the steps leading upstairs.

Charlie, after an hour of Wii, came down and, when I introduced him to the “police officers,” he got this look I could feel in my own cheekbones. “Dad, what’s wrong? What did we do?”

“Charlie, nothing’s wrong. These two nice officers just wanted to ask me a question about an incident they’re investigating. Unfortunately, I didn’t see anything.”

“Why ‘unfortunately’? Isn’t it better to not see anything?”

Commie, does that sound like anyone you know? Love that kid.

Doing my best Ward Cleaver, I said, “Charlie, we want to help the police do their jobs. We’re the good guys and the police are also good guys. So we all have to help get the bad guys.”

I glanced at Byron and caught him checking out that inch of skin over Alyse’s sweat pants. I don’t want to say I’m clairvoyant but, right then, I knew this cop was bad news.

Charlie said, “I have a sister too. Her name is Esme. She’s having dinner at a friend’s house. That’s it. There’s just four of us. No one else lives here.”

“Charlie,” Alyse said, motioning toward the civil servants downing Italian roast in our private home, “these men are detectives, not census takers.” Then to the cops, “He learned about the census in school recently.”

Then Charlie says to the cops, “They take the census every ten years to see how many Americans there are on Earth.”

Alyse and I turned to each other like: Don’t look at me. He’s your kid.

Shelby said, “Well, we’ve intruded on you folks long enough.”

But Charlie, regaining his sense of homeland security, said, “No, you can hang a while if you want.”

“Charlie,” I said, “the officers aren’t going to catch any bad guys here. They gotta hit the streets.”

Charlie said, “That’s so cool. Do you make a lot of money?”

I looked at the cops with exaggerated discomfort and said, “Why do kids just love asking embarrassing questions?”

At which point, Byron gave me a look and said, “Why is that an embarrassing question?”

I said to myself: What is this guy’s problem?

Shelby interceded, saying, “Charlie, your question wasn’t nearly as embarrassing as our salaries.”

I laughed too hard, Charlie laughed too soft, and Alyse laughed just right. Then, when the cops started leaving, Byron did another weird thing: As we shook hands, he turned his wrist in a way that flexed the muscles along his arm. He looked at his ripped arm, then at me. Who knows, maybe it was a macho weight lifter/cop move.

Alyse and Charlie escorted the officers out. I listened to the muted good-byes, the door opening, clopping steps, the door closing, an engine starting up, tires spitting gravel, and finally the return of our family’s hum of residential bliss. Right then, an odd idea began brewing in my head. Fear of being caught mixed with queasiness about Byron which mingled with a dash of criminal thrill. All three blended into a strange feeling of defiance I’d heard about in other people. It freaked me out, but I went with it. Raising my fist in the air, I said under my breath, “Pigs off campus.”

XIX.

Maryland was no Berkeley, but I think there was some tear gas on the mall before we got there. We missed the campus riots and all that. One of my TA’s told me it was all an excuse to blow off classes. I don’t know what my excuse was.

Remember that day at the end of senior year when I bumped into you on the mall and you were livid because you got a B in Bowling? What was it? You bowled something like a 250 the first day of class but got a B because you didn’t improve over the course of the semester? Your only B in four years. Sorry I laughed so hard.

Actually, I’m not sorry. Looking back, you have to admit it was funny. I honestly thought you might kill that professor.

Professor. As if the guy had a Ph.D. in Bowling.

You want to hear how much Esme is her mother’s daughter? The Binders dropped her off after dinner around nine, nine-thirty. Poking around for signs of any residual damage from Esme’s encounter with You-ey, Alyse and I asked about her dinner and she said, “Mrs. Binder kept asking me if I wanted spinach. I said no, ‘No, thanks,’ but she kept asking. ‘No spinach? Don’t you like spinach?’ I swear to God, it was like The Spinach Inquisition.”

I mean, not to be one of those fathers, but that’s kind of genius-level stuff.

Of course, the main effect of the joke was that it eased Alyse’s mind. It gave her reason to think Esme wasn’t traumatized by You-ey’s flash of Jew-hating. At least not for the moment. God knows what a kid does with something like that. Does it just roll off her back or stick in the memory banks waiting for a peak moment of vulnerability in life to pop into her consciousness and turn her into a paranoid schizophrenic?

I remember reading that schizophrenia usually surfaces in the late teens or early twenties. Jesus, how depressing is that? It’s hard enough to keep your kids alive for the first eighteen years of their lives, not to mention sane and functional. Then, out of nowhere, your happy, slang-talking, well-adjusted kid is sitting in a dorm room and starts hearing voices? Come on! By fifteen, you should be allowed to declare that your kid’s officially not defective. But no, the walk through the minefield never ends. Hell, the mere fact that a kid is born anatomically complete feels like something you’d need Penn and Teller to pull off. For that, you’re rewarded with a day of ragged relief, then you spend six or twelve months watching a human blob, during which you’re scared shitless about SIDS every night or wondering all day if you’ve spawned a vegetable. Then the kid starts smiling and you get a breath knowing you defused that pipe bomb before, one day, you float a freshly baked brownie in front of the kid’s nose because you’re supposed to keep their senses stimulated. And when the reaction isn’t what you hoped, you start looking for signs of Asperger’s or—

You reach a point where you imagine being grateful if your

kid grows up to be merely a total asshole.

Jesus Christ. I took like eighty-five varieties of first aid classes. I can do CPR on a goddamn rhino, and I still feel impotent when it comes to keeping my kids alive. My parents raised me in total ignorance. I never buckled a seat belt until I was, what, twenty-two? And yet, here I am.

And here you are.

The whole point of it all—I don’t get it. Sometimes I just think I’d be happier without being fully informed about anaphylactic shock. They come up with so many new afflictions that when one of our friends’ kids is diagnosed with one, I actually get a tiny tinge of envy. At least the dread of what seems all but inevitable is over with for them.

That sounded idiotic but you know what I mean. It’s like before my father got sick, I used to vaguely envy friends who had lost a parent. At least they’d been through it and survived. I told my father precisely that near the end, and I think it comforted him. He was worried about me, knowing I take things in the hardest way possible. When we talked in the hospital, he had so many machines attached to him making dull techno sounds, he kept saying, “I can’t hear myself think.” So one day, I lowered the volume way down on two of the machines. I mean, shit, I’m something like a doctor, right? In those few minutes, we had a great talk without getting maudlin. Or even overly serious. My dad was a pretty philosophical, realistic guy, and whatever regrets he had, he just accepted them, so I accepted them too.

That’s probably letting myself off the hook a little too easily. I fed Alyse the same assessment, but the fact is, I preferred to merely estimate his regrets as opposed to soliciting them. I didn’t ask him how he felt about his time on Earth because, ultimately, my own version of the truth was less haunting than the prospect of his. And shit, I’m the one who has to keep on living. You can’t prepare for the death of your parents but, I gotta say, I tried. For the last, oh, ten years of my dad’s life, my mind regularly detoured to his or my mother’s death. Usually, I tried to figure out: What would be the best sequence of dying? It was obvious if my mother died first, my dad would have been lost, so I guess that panned out.

It Won't Always Be This Great

It Won't Always Be This Great