- Home

- Peter Mehlman

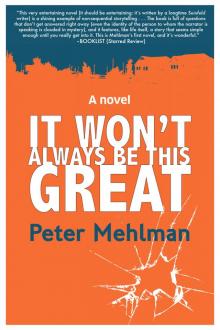

It Won't Always Be This Great Page 6

It Won't Always Be This Great Read online

Page 6

So, over lunch, I constructed the following ridiculously harsh, SAT-style analogy: Ruth Kudrow is to me as I am to Audra Uziel.

How’s that for beating yourself up?

By the way, women like Ruth having the hots for me is nothing new. I’m, like, the ultimate attractive guy to unattractive women. I’m the last person to detect someone having a crush on me, but I have noticed several super-fat women with the hots for me. It’s as if I can only get the hint from women who outweigh me.

The amazing upshot is, when these women meet Alyse, they get angry. Like: She’s too good for him. He deserves me, and no better. At best, me. The coincidence in all of this is that, as I finished my lunch, I got a text from Sylvia reminding me that I was scheduled to go to Briar Hill that afternoon. Perfect. I formulated the Audra-Ruth Kudrow analogy, and now I have to actually go and see Ruth Kudrow. I could swear I felt the last crackle of electricity from basketball short out in my legs.

I listened to sports radio on the twenty-five-minute drive to Briar Hill. The frothing host, Artie Something, had just come back on the air after his mother died. First caller: “Artie, sorry to hear about your mom. What is wrong with the freaking Jets’ offense?”

Sports radio makes me regret steering Charlie toward being a sports fan. Life as a fan exposes you to an endless horde of other fans that, eventually, just makes you feel like you’re sitting in the dumb row at school. When I was a kid, Knicks fans seemed so sophisticated. Now it’s just Spike Lee whooping up 20,000 pea-brains. And I don’t want to get into my theory right now about America’s fall reflecting the majesty of Willis Reed to the clunky Formica-handed Patrick Ewing. I mean, why can’t Charlie grow up on the sheer beauty of an Earl Monroe or the mysterious god-like Walt Frazier? Hell, one morning, I looked over at my sweet boy as he read the box scores, only to see his eyes drift off while reading an article about the coach getting accused of trying to bang team employees. What do you do?

WHAT. DO. YOU. DO?

You know, I think we’re lucky to have grown up in an America that had a trace of innocence even if it was all bullshit. The next bunch after us, those mopey Gen-Xers, got gypped out of any hope thanks to Watergate being the first thing they remember. They didn’t even get the thrill we felt from seeing that jowly psycho resign. Now people our age flail away trying to bless our kids with some semblance of a childhood, but the filth these kids see by the time they’re eight? “What’s non-consensual anal penetration, Dad?” Charlie, Charlie, Charlie. If only he could be gassed by the same illusions we had: building strong bodies twelve ways; putting a tiger in your tank . . . But no. My sweet boy, all giant eyeballs and kooky hair, has to make the leap to, Well, Charlie, that’s when someone doesn’t want to but gets fucked up the ass anyway.

All that said, I listen to sports radio because, if I’m not in the mood for music, what the hell else is there? The political call-in shows are unbearable. Even listening to people I agree with wears me out. These callers have opinions they’re too afraid to tell anyone they know, but they pick up the phone and spill it to the whole fucking world.

Did I already go off on people and their opinions?

Anyway, I got to Briar Hill around two-thirty. In the main building, I checked in with Rico Pena, a Puerto Rican guy about our age who’s been working there so long, they gave him the title of Executive Attendant. He moved to New York at 13, but his Spanish accent keeps getting thicker. “Hello Mistah Feets!” I told him not to call me Doctor, so Mistah Feets is what he came up with. I kind of like it.

Actually—and this is funny—Arnie hired a Panamanian nanny, Delmy, to take care of his only kid, Ross. She called him, “Dr. Arnold” and for years, Arnie would say, “The whole ‘Dr. Arnold’ thing makes me feel like a plantation owner. I don’t need her treating me like I’m her master, when she’s the one raising my fucking kid.”

Well, one day when Ross was like eleven, Arnie says, “Get this: Yesterday I asked Delmy to take Ross to soccer practice, and she says, “‘I’m too busy, Arnie.’” Can you believe that? “‘I’m too busy, Arnie?’” Who the fuck does she think she is, calling me Arnie? Soon this Latina broad will be telling me to go wash my dick.”

For the rest of the day, Arnie was psyching himself up to fire Delmy. He was worried about telling Ross but, when he did, Ross just said, “I don’t know why the fuck you kept her around so long.”

Anyhow, back at Briar Hill, Rico greeted me with some news: “So, Mistah Feets, your girlfriend had a mini-stroke.”

Knowing exactly who he was talking about, I said, “Who are you talking about?”

“Mrs. Kudrow, mang.”

“Oh, man. How is she?”

“Eh. She’s a little foggy, you know?”

Barely containing myself, I said, “Will she even recognize me?”

“Maybe yes, maybe no. Yesterday, I see her and she says, ‘Good morning, Yitzak.’“

“Yitzak? Who’s Yitzak?”

“I don’t know. Maybe that was her husband’s name.”

“Her husband’s name was Herb.”

“Look, mang, she called me Yitzak. Tomorrow she may call me Osama. She’s pretty verklempt.”

He saw me smile at his use of Yiddish and said, “I been saying that for years. Saturday Night Life.”

“Live.”

“Right. Anyhow, lotsa folks here like hearing me use Jewish words. Mitzvah, shiksa, kosher. Hazzer. Schvartzeh.”

“That’s great, Rico. Try not to say schvartzeh to Carolina.”

“Oh no, Mr. Lewis don’t mind. He laughs when I say it.”

Rico goes with me on my rounds to move things along. The less mobile residents tend to talk a lot. If they keep me too long, Rico has no problem playing the heavy.

XIII.

That day, I buzzed through my first six seniors, with Carolina Lewis on deck. You’re probably wondering what Carolina was doing in a Jewish facility. Actually, it’s not officially a Jewish facility. It’s just happens to be on Long Island, so it works out that way. Not to mention that it’s pretty pricey as far as these places go. Carolina got a healthy government pension, so when it came time, he liked Briar Hill best. He didn’t care that it was mostly Jews.

Carolina shook my hand like we’re good friends, which I’d like to think was true. Unfortunately, diabetes has left him nearly blind, arthritis has him moving in slo-mo, his blood pressure ping-pongs crazily, and he’s had a painful bout of shingles. “Man,” he said with a tubercular laugh, “they should trade me in for the nineteen-year-old model.” An amazing guy. Close to extinction.

Speaking of diabetes, Carolina looks a little like Jackie Robinson. Handsome, white hair. Robinson was more intense with those eyes, though.

Anyway, Carolina and I catch up a little and Rico, who knows I like talking to Carolina, goes outside for a smoke. Then, as Carolina puts his feet up for me, I notice that, on the counter of his kitchenette, there’s a skinny bottle of horseradish. The blue label has white block letters: MOSSAD KOSHER HORSERADISH. I turned to Carolina and said, “You like horseradish?”

Carolina laughed and said, “Oh God, not for me. The people who make the stuff came by and gave out free sample bottles to everyone.”

“I like it on gefilte fish.”

“Be careful. That stuff is hot enough to make a fish grow its scales back and jump off your plate. But if you want it, help yourself. I was going to give it to Mrs. Kudrow, but—”

“Rico told me about her. That’s a shame.”

“Doctor told me I’m overdue for mini-strokes. No way around it. I’ll tell you, I got a lot of stuff comin’ that there’s no way around.”

We had a moment of dead air, so I started tending to Carolina’s feet. Then, out of nowhere, I started telling him the whole story about Audra.

Maybe his mention of the 19 year-old model made me think of her. I don’t know. But I gave

him the true version of the story.

You really looked like you have a wonderful marriage.

Carolina listened intently.

Well, Audra, looks can be deceiving.

I stopped and Carolina said, “That’s it?”

“That’s what my wife said. Although I didn’t tell her that it was the look of our marriage that I said might be deceiving.”

“And you feel bad about lying to your wife?”

“Yeah. But I feel worse about disillusioning the girl.”

“Man, you can do a job of screwing your head into the ground.”

“You have no idea, Carolina.”

“Look, as far as your wife is concerned, you threw a little white lie at her about something you said that, from hearing how you’ve talked about her in the past, you didn’t really mean in the first place. No need to get all soul sick there. Marriages live and die on white lies. When the white lies end, the marriage goes with them. As for the girl, if I know anything about girls that age—and I don’t. I mean, who does?—but, if I did, I’d say if they don’t hear what they want to hear from adults, they go looking elsewhere for advice more to their liking. While you’re here doing your post-mortem on something that happened with this girl hours ago, she’s probably nine moves down the chessboard by now.”

“Kind of a mixed metaphor there, Carolina.”

“Yeah, well, I’m self-educated and never got around to literature class.”

“You’re totally self-educated?”

“I went to a tiny, segregated grade school down in Texarkana with a kindly white lady reading aloud from Heidi. Talk about tuning out. Later on, when I realized that reading and writing might have its advantages, I educated myself.”

“Heidi was such a piece of shit.”

“I refused to read it on principle.”

I got to clipping Carolina’s little toe. It was so dry and brittle, I felt like I could snap it off like the lion’s head on an animal cracker.

“Did you tell your wife a lot of white lies?”

“I was never married.”

“Really? Handsome, successful guy like you?”

“I grew up smack in the middle of three brothers and five sisters. I needed some alone time, though I didn’t plan on a lifetime of it.”

“And how do you feel about the expression white lies?”

Carolina cracked up. “It’s just like a million other expressions. The white lie is innocent, so I guess the black lie is guilty. They find out that a pork chop is actually healthier than a steak and they start calling it ‘the other white meat.’ It never ends, man.”

Rico came back, reeking of cigarettes. “Ready to roll, Mistah Feets?”

“Rico, my work here is done.”

Carolina said, “You feeling better? Did my opinion or insight or rationalization help you out at all?”

“Yeah, Carolina. It helped a lot.”

“Sure? You sound like one of those weight-of-the-world guys.”

Rico inspected my face. “He’s right, man. You got tsuris.”

Carolina engulfed my hand again and I gave it a firm shake before leaving his little home. It felt like the temperature had dropped another ten degrees. I buzz-sawed through the next few pairs of feet before trudging over to Ruth Kudrow’s. The normal dread I felt going to see her, wondering how low-cut her dress would be or whether she’d ask me to dump my wife and move in with her, was missing that day. I remember having a sick thought: One woman’s mini-stroke is another man’s peace of mind.

Ruth was wearing a wool sweater under a bathrobe. No make-up, no perfume. Just Ruth, old, blurry-eyed and, most notably, silent. A big improvement, I thought with a stunning lack of guilt. I’d once had a thought that Ruth looked a little like Barbara Walters, or what Barbara Walters might have looked like if she’d never decided to do something with her life. Now the resemblance was gone. Ruth’s demeanor had a docile flatness that seemed barely human. She was like one of those detectives on TV who view gory crime scenes with no more emotion than they’d have looking for their keys on a kitchen table.

You know, Commie? I should maybe fix you up with her.

Okay, look. Can I just apologize in advance for every ridiculous, tasteless joke I make for as long as I’m here?

In pleasant silence, I attended to Ruth’s feet. Unfortunately, my mind took one of its strolls over to the nearest minefield. I was bugged by something Carolina had said.

“You feeling any better? Did my opinion or insight or rationalization help you out at all?”

That one word. Rationalization. Why did he throw that one there? Was Carolina giving me an unbiased exoneration from my guilt or just a rationalization I could live with? I hovered over poor Ruth’s feet, my hands working without conscious commands from my head, totally consumed with what Carolina said.

Opinion or insight would’ve been a justification for not feeling like shit. But a rationalization implies that I need to ease over something truly wrong. Shit! Why did Carolina have to use that word? If only I had worked on his feet faster, I could have just taken his original assessment of what happened and felt okay about everything. If only Rico didn’t need to smoke, he’d have pushed me to work faster, and I’d be fine now. When will I learn? If someone says something that makes me feel good, just end it right there. God damn—

Ruth suddenly pulled her foot back. I looked up at her. With the blankest expression I had ever seen on a human face, she said, “I have never taken a man’s penis in my mouth. God, what a life.”

Commie, if there’s a moment to wake up, this is it.

When I thought about it later—and there was no choice but to think about it later because Ruth shorted like nine of my brain fuses—it felt like she didn’t even gauge my reaction to what had to be the most gripping start to an autobiography of all time. God, what a life, hung in the air for a thousand years, her eyes pointed my way without looking at me. It was one of the most chilling moments of my life. Even Rico whispered, “Mein Dios.”

Mini-strokes are tricky. Maybe she didn’t totally know who I was, or maybe my face sparked an involuntary motor response that tripped off something that had been on her mind for a long time. Or maybe she was perfectly lucid but too depressed from her neural jolt of grim reality to care what she said.

I didn’t know what to say, so I said nothing. Zero. I gently pulled back her foot and finished my work. Every click of a toenail sounded like a blast from a twenty-one gun salute. After the last one, I mumbled something like “Take care, Ruth,” and left.

I felt shitty about not responding to her in any way. But who can be expected to hear that and be unruffled enough to serve up an appropriate bromide?

Rico momentarily made me feel better. As we headed to the main building, he said, “Mang, I thought I’d heard it all here, but that poor Mrs. Kudrow freaked me out.”

“Yeah,” I said, “it’s terrible. Just terrible.”

Then Rico said, “You think she wants to shtup you, mang?”

So much for feeling better.

XIV.

I got in the car and my call-Alyse-and-tell-her-what-happened reflex kicked in. Esme picked up the phone and started talking to me without saying hello. Fucking Caller ID has torpedoed the whole social contract of the phone call.

“Daddy, I have to whisper because Mommy’s crazy artist, You-ey Brushstroke, is here.”

“He’s crazy, Esme?”

“Maybe. He kind of freaked me out.”

“Why’s that, honey?”

“When I was alone with him—and it was just for, like, a minute—he said something so random and weird to me.”

“What? What did he say?”

“He like, looked around at all the stuff in our house and said, ‘You bagel-biters really know how to make money.’”

Christ. It never en

ds.

“Daddy, isn’t that anti-Semitic?”

I paused for a second to drain the well of any alarm from my voice—Jesus Christ, my beautiful little girl who made her own decision not to have a bat mitzvah because, God bless her, she feels like a full-fledged deliriously happy and free American, as opposed to a persecuted minority latched to its screaming history who gets exposed to anti-Semitism in her own home. Why? Why?—“Well, Ezzie,” I said, “it may sound anti-Semitic but, you know, You-ey is from a different country and sometimes foreign people say things that they don’t mean or intend to sound bad, but it just comes out that way because English isn’t their natural language. And also, sometimes their rules of conversation are different. You know, it’s a cultural thing. Like remember in that book report you wrote about when you go to Singapore, they get mad if you spit or chew gum?”

“You mean, You-ey doesn’t, like, understand the rules here, so he said something a normal American would keep to himself?”

“Exactly! Ezzie, you’re so smart. How did you get so smart?”

“I have a really smart daddy?”

“Good answer, honey. So, don’t worry about You-ey. I’m sure he’s very nice, just a little different. Now, can I talk to Mom a sec?”

“Okay. I love you.”

“I love you, Ez.”

Alyse got on the phone and, still bottling up any hint of an APB in my voice, said, “Alyse, is everything under control over there?”

“Yeah. You-ey clashes with the decor a little, but yeah, all’s fine. Why?”

I told her what Esme said and could almost hear vital organs rising in Alyse’s throat. In a quivering whisper: “Oh my God. I can’t believe he said that. I’m sorry.”

“It’s okay. I explained it to Ezzie and she’s fine. The guy’s a mild anti-Semite but who’s not? Besides, he wouldn’t do anything really bad because you’re his only hope for any future income. So just relax and send him on his way gracefully. I was going to stop at the office, but I’ll come right home.”

It Won't Always Be This Great

It Won't Always Be This Great