- Home

- Peter Mehlman

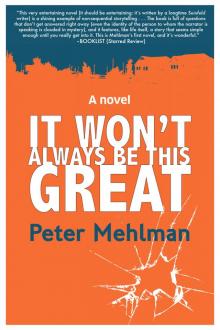

It Won't Always Be This Great Page 4

It Won't Always Be This Great Read online

Page 4

For a while, they separated. Arnie moved into an apartment in town, so he was paying a mortgage, rent, and alimony. He was verging on some dicey financial straits when he hit on an idea to drum up more business; he became Orthodox. Well, sort of. He wore a yarmulke, hung out at the Orthodox synagogue and, without ever joining, regularly engaged the rabbi about Jewish philosophy.

That rabbi, Mel Schwachter, is a good guy. If you met him on a tennis court and he was wearing a baseball cap, you’d assume he was Reform. He talked to Arnie for hours and put forth a highly sensible and forgiving theory to explain “the Asian woman.” The thing I remember about the Rabbi’s theory was that he quoted a Bob Dylan song: I’m tryin’ to get as far away from myself as I can. Rabbis love quoting Dylan. In a heartbeat, they’ll throw over the Talmud for Blood on the Tracks.

Anyway, Arnie promised to join the synagogue as soon as his finances allowed. The Rabbi would say, “Whenever you’re ready,” and Arnie would say, “Thank you, Rabbi.” Then on Friday afternoons, Arnie would leave work early, make a show of stopping in the synagogue to say, “Shabbat Shalom,” get in his car, drive to the city, toss the yarmulke in his glove compartment, and meet a few friends for sweet and sour pork on Mott Street.

Sure enough, Arnie got a slew of Orthodox patients without ever even having to join the synagogue. He said it was a case where bullshit talked and money walked.

That morning, one of Arnie’s patients in the waiting room was bent over like he’d petrified trying to tie his shoelaces. He laid open a copy of People on the floor to read it. I guess it kept his mind off the pain, reading about whatever actress adopted a Rwandan baby that week. Amazing how these starlets get on these famine-stricken country adoption lists like the poor kid is a Mike Jacobs bag. Mike Jacobs? Doesn’t sound right.

Whatever. Arnie and I share a receptionist named Sylvia Hoskett, who is, I swear, so nondescript I couldn’t help a police sketch artist draw a reasonable likeness of her even though she’s been working for us for seven years now. But she’s a great receptionist and takes the job very seriously. Once, Arnie said, “I wonder if it’s fun to be so squared away all the time.”

My first patient of the day was Audra Uziel. Remember? I mentioned before that her father brought her in with plantar’s warts when she was eleven. Now she was eighteen, a freshman at Columbia. I’d seen her two or three times when she was a tween. Plantar warts are very common in children, caused by the human papilloma virus, the same one that causes herpes but in a different manifestation. They can be treated with topical medication, cryotherapy, or surgical excision. Some people try a homeopathic ointment from the outskirts of science, but it’s crap. I had treated Audra when she was eleven but, by fourteen, she was back in my office. That was the first time she’d come alone, which didn’t surprise me. I’d seen her father a month earlier, and when I asked after Audra, Nat shook his head and said, “Audra is very independent. Too independent.” Among other examples, he said that she “wanted to dress immodestly.”

Imagine that scandal in the Uziel home, huh? Here the guy makes a killing selling hot clothes to little girls, and when his daughter wants to be on the same playing field as his customers, he puts the lid on her. And, believe me, this wasn’t a case of the hot eighth grader who realizes that anatomy is destiny and wants to put the sexy merchandise in the front window as much as possible. Audra was a plain-looking fourteen-year-old. Longish face with flat, pale skin, and kind of short teeth that made you want to reach in with a pair of pliers and pull them down further from her gums. But I guess all fathers think their daughters are gorgeous and Uziel was no different. He didn’t want her turning into Miley Cyrus or Hannah Montana (whatever her real name is). I can’t keep that shit straight.

That said, Audra and I had gotten along well since the first time her father brought her to the office. As you can imagine, most kids assume podiatrists must be freaks to devote their lives to the stinkiest body part. Oh—you’ll love this—you know those scented cardboard pine trees you see dangling from mirrors in taxis? Well, when I get a child in for the first time, I hang one of them around my neck. Then I say, “You think I can treat your stinky little feet without something that smells nice around my neck?” The parents usually laugh, so the kid decides I’m funny too. With Audra, it was the opposite. Eleven years old and she got the joke immediately. Her father? Nothing.

Now, that first time she came in without her father when she was fourteen, I was happy to see her, but a little bummed that her warts had come back.

“So, Audra, your stinky feet are acting up again?”

“Actually, no,” she said. “My feet are fine. I’m here because I wanted to apologize to you.”

“Apologize? For what?”

“My family. Duh?”

“Duh? Well, I guess I’m seriously duh because I don’t know what your family did to precipitate an apology.”

Audra smiled. “Precipitate. I like how you said that word. So official and professional-sounding.”

“I’m an official professional in the foot-care field. But, even with all my expertise, I still don’t—”

“My idiotic brother badgering you on the street because you were eating a cheeseburger?”

“Oh, that?”

“Yeah, that.”

“That was about six years ago, Audra. He was just a boy at a stage when he was a little too serious about stuff.”

“A little? You think? You should see him now. He’s got the beard, the black suit, the whole accessorized fanaticism.”

“He’s gone ultra-Orthodox?”

“More like ultra-Taliban-Orthodox. He’s living in Crown Heights. I see him once a month when he deigns to come to the house for Shabbat. I say ‘deigns’ because, in his eyes, our ‘merely Orthodox’ home may as well be a mosque. But he comes because he loves my father for setting him on the path to devout lunacy.”

“Does he try to convert you?”

“No. I’m too far gone. He sees me as an eighth grade whore.”

When she saw in my face that I was fishing around for a reaction, she pressed her case.

“And then my father has the nerve to come to your office and give you shit for defending yourself against his whacked son?”

“Audra, take it easy. Don’t get worked up.”

Again, she smiled. “You think because I said ‘shit,’ that means I’m worked up?”

I had a thought at that moment: As soon as kids realize they’re smarter than their parents, growing up becomes infinitely more difficult. Audra was in for a tough road.

I took a breath and said, “You’re a smart cookie, Audra. And you know you’re one of my favorite patients. Not that ‘my favorite patients’ is an overly competitive category.”

She laughed out loud at that one, reminding me of the time she’d laughed aloud at my old air freshener joke.

“Well, you’re my favorite care-giver, and I have a collection of them now.”

“Really? Why? Are you okay?”

“I think I’m better than okay. But my father doesn’t agree, and you know how when people make a lot of money, they think their opinion is more valid than everyone else’s?”

Wow.

“Well, my dad has various health professionals refereeing our difference of opinion regarding my well-being.”

“What’s your dad’s opinion of your well-being?”

“He’s not sure. But, seeing as I just want to be normal, he assumes I’m not normal.”

“Normal? Meaning ‘not Orthodox’?”

“Among other things. He even brought me to an endocrinologist thinking maybe my problems were glandular. It would certainly be easier to explain me if my non-existent problems were not only real but somehow physical.”

“Have you tried explaining your reasons for your—I don’t know . . . Secular leanings?”

“I can’t.

I don’t want to hurt him.”

“Well, that’s thoughtful, Audra, but he’s probably stronger than you think.”

Audra slumped and looked off to her left, where my joke of a diploma from podiatry school hung on the wall. I glanced over at it and thought of how my remote-controlled life had led to another strange moment. This one took the form of sitting with a teenage girl and having one of the most adult conversations I’d ever had.

Without taking her eyes off the diploma, Audra said, “Would you be surprised if I told you my dad didn’t have a bar mitzvah until he was forty-two?”

“I would, um, yeah, be very surprised. Shocked . . .”

“That’s how un-Jew-y he grew up. He hardly set foot in a synagogue until the baby who was to be my older sister came out stillborn. That’s when my father put on the yarmulke he still wears today and became Orthodox. And when I came out fifteen months later, my father gave God full credit. So, I can’t really tell my dad that the tragedy in his life happened to him, but not to me. And I can’t ask him, if he got to have a childhood without the eyes of God bearing down on him, then why can’t I? He’s not that strong.”

Nat’s statement flashed back to mind. I never failed at anything. I did mention that, right? The day Nat, calm as a Mafioso, confronted me over my zinger aimed at his son . . . he was a mess like everyone else.

IX.

I looked at Audra, lost in her own little dilemma. She’d confided a lot to me and I sensed her beginning to feel as though she’d overstepped. I said, “I guess our dads went in different directions. Mine was bar mitzvahed at the normal age, then dismissed the religion. He died less than a year ago and, just before the end, a rabbi came to his hospital room, but my dad waved him off and said, ‘Religion is for people who can’t accept that this is all there is.’ I loved him so much when he said that. In fact, when he died, one of the nurses told me he was in a better place, and I said, ‘No he’s not. Yesterday he was in New York. Today he’s dead.’ My dad would have loved that.”

Audra looked up with a kind of wonder and said, “I wish I’d said that! Can I steal it?”

“It’s yours,” I said.

“By the way, I’m sorry about your dad.”

“Thanks. The night before he died, someone at the hospital stole his wedding band. And I keep wondering if, in his drug-clouded state, he felt the ring twisting off the finger where it had been for 52 years, and if he thought, I knew I should have sold the damn thing.”

Audra laughed.

Then I had a thought: “Audra, how did you know about the thing with your brother and the cheeseburger? You were like eight at the time.”

“My mom told me the story a few days ago, after I asked her when my brother became such a freak.”

I guess I looked stricken because Audra quickly added, “Oh, don’t worry. My mom wasn’t saying that you sent him spiraling to Crown Heights. She just included that one thing on the timeline of his anti-social highlight reel. I know it happened a long time ago, but just imagining that scene on the street bothered me so much. And I know this is sooo teenager-y, but I really wanted to apologize to you. I told my mom, and she said, ‘If you feel like apologizing, do it.’ See, I can talk to her about this stuff because, even though she does the Orthodox thing, I don’t know if she believes in it or if, between my father and my brother, she just never knew what hit her. I don’t ask because . . . let’s just say I live in a fragile household.”

At that point, I cut off my intimate look inside the Uziel family because I’m someone who can look away from car wrecks. “You know what, Audra? I accept your apology. Obviously you feel an apology is merited, so I’ll respect your judgment.”

“Good,” she said getting up. “Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have gym.”

Audra never came to my office again throughout high school, although I did bump into her once at a smoothie joint where she told me her father had suffered a mild heart attack. I was surprised because he’d been coming to my office once a year for eight years and had never once mentioned any changes in his health. Not that pushing around his flanges would affect his heart. But I asked the question like I’m supposed to and he didn’t come clean.

Now Audra’s in her first semester at Columbia. Commie, didn’t you apply to law school there? Whatever. So, this morning, she comes to my office wearing no make-up, a long skirt, bulky sweater, and woolen mittens. She wasn’t “immodestly dressed,” but she definitely looked different from her fourteen-year-old days. Her face didn’t seem as long, her hair was short and stylish, and even her teeth somehow looked like they’d figured out where they ought to be hanging in her mouth.

She gave me a hug—a generation of compulsive huggers, these kids today—and said, “You been away? You have color.”

“Oh no, it’s probably endorphins from basketball last night. I had a great night.”

She nodded like: Still playing hoops? Not bad. Then she took her mittens off, and I saw a ring on her left hand.

“Audra, are you engaged?”

“Huh? Oh, the ring. No, I just wear it to keep guys from hassling me. Lots of girls do it. It’s jewelry as repellent.”

She glanced at one of my hanging Bose speakers that wafts out the pre-programmed music I pay for every month like an idiot. It was a song by Gwen Stefani. I said, “I love this song, but what does that mean, ‘I ain’t no Harlem Black girl?”

Audra cracked up. “It’s not ‘I ain’t no Harlem Black girl,’” she said, wheezing with giggles. “It’s ‘I ain’t no holla back girl.’ Oh my God! That is so funny!”

“Holla back girl . . . What the hell does that mean?”

“It’s so not important.” Then she shook her head and said, “You know, even at your age—not that you’re old!—but you still make an effort to be cool. I like that you do, but at the same time, I would love to reach an age where I don’t have to be so compulsively up on everything.”

“I gotta say, I think ‘Harlem Black Girl’ is a better lyric.”

“Well, if you ever bump into Gwen . . .”

“I hear her husband’s Jewish.”

When I said that, Audra stopped smiling. Drearily, she mumbled, “Score. Another assimilation three-pointer for us.”

“You know your basketball.”

I sensed that treatment, as at our years-ago last appointment, was not going to be happening.

Audra shifted in her seat and said, “Last week, I saw you and your wife at The Flotilla Café. She’s really pretty.”

“Thank you. Why didn’t you come over and say hello?”

“You really need the image of my plantar warts over dinner?”

“I’m sure I wouldn’t have had flashbacks of your pre-adolescent feet.”

“Actually, I liked just watching. Your wife was talking about something for kind of a long time and you seemed so attentive.”

“She represents artists and she was telling me about this lunatic Balkan client who, by the way, may be visiting my house today, which doesn’t thrill me.”

“Wow. That’s incredible.”

“What?”

“You instantly remembered what the conversation was about! That’s amazing. I mean, don’t you ever look at other couples and see how they zone each other out, nodding and picking at their food? Or worse, neither of them talking at all? But you still really listen. That’s so rare. You really look like you have a wonderful marriage.”

Audra’s eyes reminded me of how Alyse looked at me when we first started dating. That crazy Wow-this-girl-may-be-into-me feeling. And now 850 years later, there it was again. I felt a big hairball of self-esteem blow through my office.

So, what did I do with that feeling? I’ll tell you what I did. I maimed it by saying an unbelievably stupid thing: “Well, Audra, looks can be deceiving.”

I swear, I literally saw her expression go from what

ever it was—sweet admiration, I guess—to disillusioned nothingness. I mean, before I knew it, I was saying, “Have you been wearing unusually high heels?”

A life-affirming discussion morphed into a professional foot care appointment like that, and then she was gone.

X.

When I heard the front door of the office close behind Audra, I went quietly beside myself. How could you say something so stupid? Looks can be deceiving? The girl’s obviously dating someone and in love and worrying if the feeling can last and looking to you for reassurance and you give her “looks can be deceiving”? What a fucking idiot.

Over the years, I’ve managed to say more than a few stupid things like that. When I was in my twenties, I was a faux pas machine. Alyse swears I wasn’t, but I’m more tuned in to my own stupidity than she is. And besides, I’ve always been ultra-careful around her because, no matter how long we’ve been together, I’ve always guarded against blowing things with her. I’m still guarding against blowing it. So, most of my faux pas happened out of her earshot, when the censor in my head was taking a break from the high stakes game of my relationship. But still, on the rare occasions that I still do shoot off a doozy, I can’t help torturing myself over it. I go over it and over it, thinking about the way it should have come out in the first place. Then I’m like: When are you going to learn to think before you speak?

Before my next patient, I drummed up one rationalization to tide me over for a while: Talking to Audra made me feel like the twenty-one-year-old me who said stupid things for a living.

Anyway, I barely remember the rest of my patients from that morning until Rick Burlingame came in. He’s a Wall Street guy and rich enough to hardly ever go near Wall Street anymore. I guess he spent most of his time at the gym because he had veiny biceps bubbling up under his skin. He’s about 45 or so, that age when being muscular starts looking sickly. What does it say about a society that tells guys to turn their love handles into rock hard abs? Don’t love handles sound nicer than rock hard abs?

It Won't Always Be This Great

It Won't Always Be This Great