- Home

- Peter Mehlman

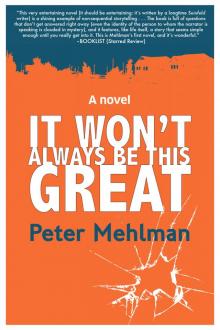

It Won't Always Be This Great Page 11

It Won't Always Be This Great Read online

Page 11

At that point, it dawned on me just how much explaining I’d have to do if, somehow, I wound up being arrested, tried, and convicted for my vandalism, or my malicious mischief, or wherever they would wind up throwing the book. After all, in a little over twelve hours, I’d lied to my wife, my kids, my mother, and the police.

Then I had another thought: If I get nailed, I’ll just say, Look, I hurt my ankle, got mad, threw a bottle through a window, fled the scene, and lied about it to everyone I know. Not my best choice ever. But it is what it is.

Were you awake for It is what it is? That trash phrase has become the unimpeachable get-out-of-jail-free card for any offense you can name. If that phrase was around in 1953, the Rosenbergs would be living happily in Boca right now.

Besides being revolted by the idea of moving to Florida, the great thing about my mother is, I never know exactly where she’s going to come down on any issue. She’s a true wildcard. Like in the Clinton-Monica thing, my mother said, “I don’t know why he didn’t just say he had sex with her. That’s why these men run for president, so they can have affairs. You think they want to give speeches and drop bombs? No, they want to cheat. Roosevelt, Kennedy, Eisenhower—they all took the job so they could cheat. And Clinton? When he was running, everyone knew that he cheats. All he had to do was say, ‘Yeah, I had an affair with an intern from Beverly Hills. What of it?’”

Sure enough, on the issue at hand, my mother said, “I don’t see what the anti-Semites hope to accomplish by throwing a bottle through the window of a clothing store. What do they think is going to happen? We’ll throw up our arms and say, ‘You win. I’ll convert to Protestantism first thing in the morning?”

I told my mother about the rally and she said, “I don’t see what a rally is going to accomplish either but go, enjoy yourself.”

III.

Alyse and I decided to leave around 11:30 for the noon rally. These things never start on time anyway and, if we’re late, so what? I did wonder how Nat Uziel could be on time. From the synagogue to the store is about a mile and a half, and that much walking would hurt his feet.

I didn’t get into this earlier, but I did a pretty big job on his overlapping toe. It involved balancing the soft tissue supporting structures around the joint at the base of the toe which, in turn, included tendon transfers, joint capsule release, and ligament tightening. Plus, I had to cut through the bone, reposition it to the correct alignment, and stabilize it in place with screws.

You probably didn’t need to hear all that, huh? I was showing off for you, but the truth is, I don’t do surgery anymore. When I first started practicing, I went in on a surgical center with a slew of other guys and did several foot surgeries a week. Then, maybe five years ago, I dislocated my index finger playing hoops and couldn’t do surgery for two months. I didn’t want to take the chance of getting a malpractice suit for dropping the scalpel clear through someone’s arches. To tell you the truth, I did previously dodge a bullet in that area. I started to operate on the wrong foot of a college kid. He actually played football for Hofstra. Punter. I went as far as making an incision on his good foot before it dawned on me, I saw this kid play. He punts lefty. Shit!

I broke into cosmic panic before somewhat calmly sewing up the incision and managing to focus on the original task at hand. Later, I sat down the kid and his family and came clean about my mistake. Somehow, I got lucky enough to fuck up with the right family. They correctly assessed that no harm was done and didn’t press the matter.

Of course, I didn’t charge them for the procedure. I took some solace in the fact that the kid graduated as the sixth best career punter in Hofstra football history. Last I heard, he’s a mortgage broker. He probably wishes he’d sued.

Anyway, during the time of my dislocated finger, I took off from surgery and solicited business elsewhere to defray the loss of income. That’s when I got the work at the three Assisted Living places, which turned out to be more lucrative than the surgeries. I know some podiatrists look down their noses at retirement homes/assisted living facilities but, really, someone had to do it and what more did I have to prove? I did surgery for a bunch of years, I’d proven I wasn’t just some quack. So I stopped operating altogether.

I’ll tell you what. Remember that book I mentioned about doctors reaching an age when they start losing it? Well, I’m bumping up against that age now, and just realizing that made me feel even better about giving up surgery.

Selling off my share in the surgery center also made for a handsome payday.

Long-winded point is, no matter how well the surgery went, Uziel’s foot would hurt. Of course, considering his heart condition, the walk would be a good thing. So there you have it, good and bad in everything.

Maybe not everything.

I should have just spent the day with my ankle elevated on a couch, but I compromised. We drove about halfway there while all the Orthodox were still at services and then walked the rest of the way.

At around eleven, Alyse and I told Charlie about the rally. And, of course, he did know what a rally was outside a sports context because kids know everything. “So, because of what happened at the store where you told the police you didn’t see anything, there’s going to be a big rally? That’s awesome. It’ll be like the Boston Tea Party, right?”

“Yeah. Without the tea. And not in Boston. And not a party.”

During our drive to the rally, Charlie asked why windshield wipers are called windshield wipers because they don’t really have anything to do with the wind. I was about to say something about how the glass protects against the wind, but instead I said, “You’re right, Charlie, it makes no sense. That’s a fantastic observation.”

Charlie shrugged and said, “Actually, I’m pretty surprised no one ever thought of that.”

I think that was the kind of conversation that previously would have made me start worrying about my kids thinking I’m a schmuck. Remember I told you I used to worry about that? Even if that conversation had taken place a week earlier, I would have started thinking, Jesus, his conclusion was more grounded than mine. Eventually he’ll stop looking to me for explanations of life altogether. Being an unreliable source. That’s where I’m headed.

But that Saturday, I didn’t feel like that. All I thought about was how lively and alert my kid’s mind was. There he was, eight years old, and already he had an eye out for the little mistakes of the universe. Felt euphoric. Look what’s going on in my little offspring’s head!

In fact—and this is really great—not long after that, maybe a month, Charlie said to me something like, “Everything between midnight and noon is called morning, but after that the day is divided into afternoon, evening, and night. It’s like morning is kind of greedy, isn’t it?”

I swear, I wanted to pick him up and squeeze him like Haystacks Calhoun.

IV.

My ankle was kind of throbbing, so we drove through a couple of back alleys and managed to park a few blocks from Nu? Girl Fashions without being seen by the Yarmulke Squad. You’d think someone had declared martial law and we were driving after curfew.

Coincidentally, we hit Stratification at almost the exact point at which I’d gotten the cab the night before. I had a momentary thought of pointing to some tree root in the ground and telling Alyse, “That’s what I tripped over.” But, if I were caught, this particular lie would border on psychotic, so I said, “This is where I got the cab last night.”

Alyse nodded without so much as a trace of piqued interest on her face. I noticed because, after she had a night to sleep on it, I was trying to see if anything in my story wasn’t adding up for her. I don’t know why it wouldn’t have added up aside from my instinct to assign Alyse superpowers.

It wasn’t surprising that we weren’t the only non-Orthodox walking to the rally site. In fact, more than a smattering of non-Jews was present. I (cynically) put it down to a smart busine

ss decision, but I’m sure some people were genuinely concerned about our little town’s sudden spike in crime. There had been some typical teenager hijinks, but I couldn’t remember a felony within the zip code for at least six years. The Nassau County DA prosecutes something like thirty thousand crimes a year, but our little town? Nada. The last real case was an investment whiz a few blocks away from us who was cuffed in his home for embezzling a million dollars. And, let’s face it, that’s a pretty unambitious swindle by today’s standards. Maybe he wasn’t such a whiz after all. I presumed he was because he went to Wharton, which is ridiculous because, let’s face it, the only thing MBAs learn in business school is how to run a meeting, right? At least I came out of grad school knowing my way around a human foot, for God’s sake.

My westward limp on Stratification was fairly pronounced and Charlie grew concerned. “Are you okay, Dad?” I assured him I’d been through this a zillion times and I’d be fine, but he persisted, “You’ll be able to play hoops again?”

The question didn’t surprise me. Charlie tells all his friends that his dad “has game.” It’s cool for him partly because his friends’ fathers are all relegated to golf and partly because Charlie finds basketball impossible. He didn’t inherit my hand-eye coordination or leaping ability. I give Alyse shit about that all the time because, obviously, it’s her fault. She came from a long line of earthbound Hebrews. Seeing her father try to play tennis down in Boynton Beach—

Did I mention that Alyse’s parents moved to Florida? We visit once a year. More than that would be carcinogenic. The first time we took the kids down there, we went to a restaurant near their condo and a seventy-five-ish guy at the next table pulled his pants down and shoved a syringe in his thigh. Right there in the restaurant! Esme, who was six at the time, said, “Eww, gross!” The guy looked at her and said, “It’s not gross. It’s something I need.” At which point, Alyse walked over and whispered in his ear, “Trust me, my daughter only said what everyone else in the restaurant was thinking.”

I think I told you before, she’s got cojones.

Anyway, after assuring Charlie I was fine despite my limp, he started imitating my limp. I mean, he overdid it like crazy. He looked like Ratzo Rizzo in Midnight Cowboy. Alyse was laughing so hard we stopped for a second so she could get a grip. She didn’t want to be seen giggling en route to such a serious occasion.

We actually sat on a bench outside the popular (and closed, of course) Belly Deli. When our giddiness over Charlie’s limp passed, he asked if the detectives from the night before would be at the rally.

“That’s a good question, Charlie,” I said. “You know, they might come because sometimes a person who commits a crime likes to return to the scene.”

Again I glanced at Alyse for her reaction. Nothing. Charlie, on the other hand, was flabbergasted. “Why? Wouldn’t he be worried about being caught?”

“Well, he should—”

“Or she should,” Alyse interjected, never wanting to shortchange the capabilities of women.

“Yes, he or she should be worried about being caught, but I guess criminals aren’t as smart as you, Charlie.”

So Charlie says, “That’s why they’re criminals.”

I swear, Commie, you gotta wake the fuck up and meet Charlie. It would be well worth your while.

Among many other worthwhile reasons for you to wake up, of course.

Anyway, so, we wound up on the bench for 10 minutes. It was great, the three of us just sitting and jabbering away. When we got moving again, my ankle felt colder and creakier. I was hoping Charlie wouldn’t start imitating my limp again when I turned and saw Nat Uziel with his wife, his ultra-Orthodox son Jason, and Audra.

A beam of Oh shit ran through me. Uziel skipped introducing his family and said, “The foot doctor is limping.”

Charlie piped up, “He sprained his ankle on a tree root. He’s on the DL from basketball for two weeks.”

Audra looked at me and said, “That’s a shame. You played so well Thursday night.”

I felt Alyse look at me like: What do we have here? With my first tinge of guilt that day, I said, “Audra and her dad, Nat, are patients. She had an appointment yesterday, and she thought I looked like I had color, so I told her no, I’d just played basketball the night before . . .”

Alyse, enjoying my mini-squirm, said, “And you mentioned that you played well.”

“Of course. I tell everyone when I play well. Patients, custodians, cashiers. They all know my stat line.”

“It’s nice to meet you, Audra,” Alyse said with her warmest smile.

Audra looked at Alyse with what I took to be hero worship and said, “Likewise. Your husband is a really great doctor.”

Alyse looked at me with the tiniest widening of her eyes: This is the girl whose love life you thought you derailed? Then she turned to Audra and said, “Thank you. This is Charlie.”

Audra looked at Charlie and smiled. “Hey, Charlie.”

“Hi.”

Audra introduced her mother. The only introduction left was Jason, but she wasn’t leaping into that rat’s nest. Jason, with his pais and beard and black suit and tsit tsit, stood rigidly alert, eyeing my wife and kid as if they were Hezbollah. Sarah motioned to introduce Jason but Nat overruled her, “I appreciate all of you showing your support in light of last night’s heinous act.”

At that, he turned and walked away, his family dragging along behind him.

Heinous act. I flashed back to the cheeseburger incident. The over-the-top phrase that day had been vicious barb.

Alyse, thinking the same thing, said, “Boy, that guy must have the hysterical edition of Roget’s Thesaurus.”

I nodded and Alyse added slyly, “But his daughter’s lovely. Your type, kind of.”

Too fast, my head turned to her. Caught.

“So, when you said ‘looks are deceiving,’ were you talking about us?”

Charlie said, “The guy with the beard was creepy.”

Grateful for his input, I said, “No, he’s just very religious.”

“Still, he was creepy.”

We started walking again and when Charlie skipped a few steps ahead, I said to Alyse, “I can’t believe how easily you see through me.”

“You were way too upset yesterday about what you said to her. I couldn’t figure out why until now, when I saw her.”

I shook my head, feeling sick.

Alyse said to me, “Honey, relax. It’s alright. A young college girl adores you and you flirt. It’s okay. Really, it’s reassuringly human. Of course, I’d rather you not pooh-pooh our marriage as part of your flirting, but—”

“Believe me, that’s the part that’s killing me. I know some dopey comment from a podiatrist isn’t going to unhinge a smart girl like her. I just . . . I’m sorry. I’m an idiot.”

“No, you’re just rusty.”

“Rusty?”

“You know,” she shrugged, “when it comes to flirting.”

“Jesus, stop saying that word. Besides, you can’t be rusty at something you were bad at to begin with.”

Charlie turned around with a “look-at-me!” look and started imitating my limp again. He was pretty good at it, I’ve gotta say.

Alyse nodded at Charlie (Well done!) and said, “Believing you were bad at flirting is what made you good at it, but I don’t think we really need to get into that now. I mean, this is the first such conversation we’ve ever had. That’s pretty amazing.”

“Some people would find it weird.” Then, “Do you find it weird?”

Alyse gave it a thought and said, “I don’t think about relationships very much anymore. But I’d say the one thing I’ve decided in the last, I don’t know, twenty-five years, is that a good relationship occurs when both people think the other is too good for them.”

“What about when only one person

feels that way?”

“I don’t know. I have no experience with that.”

You know, Commie? When I’m in a discussion like that, I’m not really thinking. Actually, I’m hardly ever in a discussion that actually touches on the deeper subjects of my life as it’s being lived. But my point is, in the middle of it, I’m thinking, but I’m not—what’s the word? realizing? deducing? those still aren’t the right words—I’m playing ping-pong but only thinking about my next shot without seeing the whole game? How I got through the SATs with such shitty analogies is beyond me. The thing is, as I’m telling you this, I’m realizing how well Alyse handled that conversation. I feel like, if it’s possible, she’s gone way up in my book just over the course of telling you this whole story.

Really, you should think about opening a therapy practice right here in this room. You lie there and people just come in and talk like I am. I guarantee the epiphanies would come easier than with some shrink chiming in every two minutes. You could have a booming practice, scheduling patients twenty-four hours a day. You want a double session? A quintuple session? No problem. David Moscow, Doctor of Vegetative Psychology, can squeeze you in.

Just because you’re not conscious doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be economically viable.

V.

Anyway, as we got close enough to Nu? Girl Fashions to see big clumps of people milling around, Charlie stopped limping. Like me, he only entertains for select audiences. He stopped and waited for Alyse and I before asking if either of us had a TicTac.

“You’re concerned about the freshness of your breath?” I asked.

“I don’t know. A little.”

Alyse dug around her pocketbook for anything minty while I gave my standard passing thought to whether I’d one day look back at this moment as the first sign of my son having wicked OCD. Alyse pulled out a butterscotch sucking candy from 1982 and Charlie said, “That’ll do.”

As we were waiting at the last red light before the rally, Carl Penza, the Nassau County executive all dressed up in a boxy, grim suit, stopped beside us with a somber entourage of two men and a woman in their mid-twenties along with a uniformed cop so buff his badge looked like it was about to pop off his chest. Personally, I preferred when cops were fat and out of shape, like in Manhattan during the ’80s. They seemed more approachable. Now they’re all lifting weights, pumping pound for pound with the convicts they bust. They’re scarier to me now than they were when I was a kid. Of course, that may also just be the criminal in me talking.

It Won't Always Be This Great

It Won't Always Be This Great